Nationwide, a month of protests against police brutality and senseless violence against the Black community continue after the brutal murder of George Floyd. However, racial injustice extends far beyond police brutality. Racial disparities in vulnerability to COVID-19, and the health consequences and mortality resulting from contracting it, shine a harsh spotlight on the structural inequities facing people of color – and especially Black people – in America. In this week’s blog post, I dig into some of the literature around the racial disparities seen in COVID-19, though this is only one example of systemic racism in America.

Persistent and stark disparities have been noted in both COVID-19 infection and mortality rates. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Black Americans have been dying at about 2.4 times the rate of white Americans, and in Minnesota, the age-adjusted death rate among Black people is 70 per 100,000 vs 20 deaths per 100,000 people for whites. In Maine, the nation’s whitest state, Black people are 24 times more likely than white people to test positive for COVID-19. These disparities are striking – with a paper in JAMA finding that in Chicago, COVID-19 incidence rates are highest among Latino (1000/100,000) & Black (925/100,000) individuals, and markedly higher than the rate among white residents (389/100,000). That paper also found that mortality rates are markedly higher for Black individuals (73/100,000) vs. Latinos (36/100,000) and whites (22/100,000).

Early reports of such disparities led to pressure for Medicare to release a detailed breakdown of COVID-19 infections/deaths by race in late March. However, Medicare officials still have not released that data. The first national-level data released regarding racial breakdowns of COVID-19 cases was from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in mid-June. The CDC found that 33% and 22% of the country’s early cases of COVID-19 were in Latino and Black individuals, respectively, rates nearly DOUBLE each group’s share of the population.

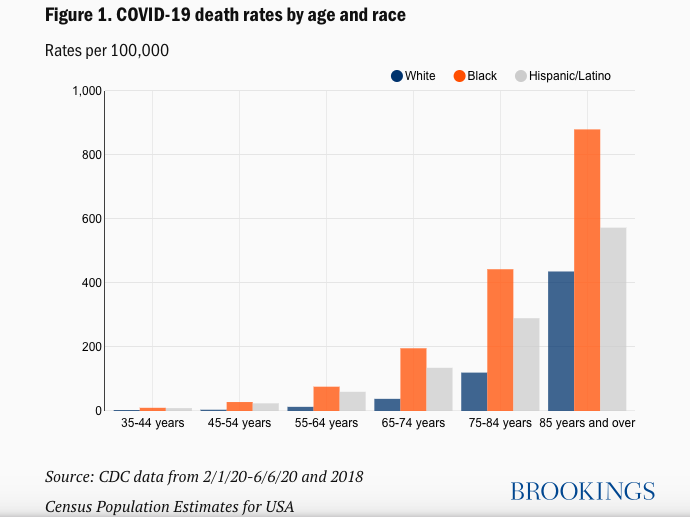

Data from the Brookings Institution indicates that death rates by age and race show marked disparities – which are made even clearer by looking at the ratio of death rates based on racial breakdown, where the disparities – especially among younger age groups – become strikingly clear: you can see that in Figure 2, below, the ratio of Black to White deaths for those age 35-44 is around 10-fold – indicating how stark these mortality rates are for Black people in America compared to whites.

The COVID Racial Tracker, a joint project of the Antiracist Research & Policy Center at American University and the COVID Tracking Project, compares each racial/ethnic group’s share of infections or deaths (to the extent known) with their share of the overall population. An important caveat here is that the analysis only can explore disparities when race/ethnicity is reported, which is not nearly enough, with 48% of cases and 9% of deaths still having no racial data. States have to do much better at reporting racial data to assess the depth of these disparities, but, until then, the existing data provides the best snapshot of existing disparities.

The COVID Racial tracker shows that across the US, deaths from COVID-19 in Black Americans are ~2x more than should be expected based on their share of the population. In Wisconsin, Michigan, Missouri, and Kansas, the death rate is more than 3x greater. By contrast, white deaths from COVID-19 are lower than their share of the state population in 37 states and Washington DC.

Where do these disparities come from?

Systemic racism and structural inequalities contribute to the disproportionate burden of COVID-19 on racial minorities in a number of different ways. I’ll name a few:

- Minorities – especially Black, Hispanic, and Native American individuals – experience the highest levels of poverty in America.

- Racial/ethnic minority populations face a disproportionate burden of comorbidities, including, but not limited to diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and asthma, all of which make COVID-19 more severe. Poorer access to fresh fruits and vegetables, and greater likelihood of living in areas with less access to clean water and air, exacerbate and can cause these conditions.

- Due to structural factors, racial/ethnic minorities more often live in urban, crowded conditions, where it is easier to contract COVID-19.

- Racial/ethnic minorities are more likely to be employed in public-facing occupations, and essential jobs that make physical distancing impossible. The ability to isolate in a safe home, work remotely with full digital access, and sustain monthly income is a privilege many racial/ethnic minority members do not enjoy.

- Black workers comprise approximately 11.9% of workers overall in the US, but represent 26% of public transit workers, 18.2% of trucking, warehouse, and postal workers, 17.5% of health care workers, and 19.3% of social services workers. For more information about this breakdown, click here.

Beyond the concrete ways in which structural racism stacks the odds against BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) in America, long-term discrimination and fear can also physically alter the body’s chemistry, disrupting the stress hormone cortisol. Such chronic stress contributes to other health conditions such as diabetes, obesity, depression and other mental health issues, and obesity, furthering the disparities BIPOC face in America.

Even following ‘simple’ guidance to wash hands to reduce the risk of COVID-19 is a challenge in poorer communities where “high water bills, or lack of access to clean water altogether, make compliance impossible… Households in hard-hit Native American communities, particularly in the Southwest, are 19 times more likely than white households to lack running water,” explained Vickie Mays, a health policy professor at UCLA. In Detroit, since 2014, more than 140,000 homes have been disconnected from running water service due to a debt collection campaign, and as of March 31, there were still 1,000s of residents without running water despite a pledge to restore water to residents due to COVID-19.

A personal reflection on how to move forward

I don’t have any answers right now but I have lots of questions. These are questions that must keep being asked, and questions that must be answered. Personally, I have been in a period of reflection, education, and awakening to the pervasive injustices against Black people in America. From reckoning with senseless killing and police brutality against Black Americans to confronting dramatic racial disparities from COVID-19 in a project I’m working on for the state of Michigan, I realize that confronting structural inequality, discrimination, and racism is something I need to take with me in all the epidemiology, infectious disease and vaccine-related work I engage in going forward, both in research and in daily practice.

In my role as a volunteer contact tracer for the state of Michigan, I have seen in real time the ways that structural racism and poverty exacerbate COVID-19 disparities and pose challenges for controlling the spread of the pandemic. I call individuals who have contacted a positive COVID-19 case and inform them of their exposure, instruct them to quarantine for 14 days, and monitor themselves for symptoms. It wasn’t until these phone calls – where I told people to stay home only for them to respond “I’ll lose my job”, “I have to work to feed my family”, “Will I be compensated for staying out of work?” — that I realized that self-isolation and social distancing are impossible for so many. The fact that Black Americans disproportionately represent essential, frontline workers furthers the disparities in the likelihood of contracting COVID and in the likelihood of getting really sick and dying from it.

The pandemic has highlighted the tip of the structural racism iceberg in America. To fight COVID-19 effectively and rectify the racial disparities in its impact requires addressing structural racism in intention and in practice in our pandemic response and in the design of public policy and investment of philanthropic and other resources. I am pledging to use my voice to shine a light on racial disparities in health and the lived experience of Black communities in America, and practice more equitable science and research every day. I challenge you all to do the same.

Leave a comment